Outcome

After inflation reaching a 40-year high in the United States, the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates in their March 2022 meeting for the first time since 2018. They increased the policy rate by a quarter percentage point from near zero (although some leading economists had argued for a half percentage point). Furthermore, while early this year economists expected three increases in the policy rate during 2022, now the Fed is expected to increase the rate six more times this year. Similarly, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are also expected to see their policy rates up. Clearly global interest rates are on the rise.

In Australia, the year-ended C.P.I. inflation (trimmed mean) remains at 3.5 (2.6) per cent as this is currently measured quarterly. Yesterday (March 30th), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released a note in which it’s stated that they will produce monthly indicators of wages and salaries and that the A.B.S. will examine the feasibility of a monthly C.P.I.. This would be a great innovation. Absent those figures, we know that the Australian economy is recovering strongly from the pandemic. Unemployment is at 4 per cent and expected to hit 3.75 per cent (a 50-year low) by September 2022. Currently, the Australian economy has 200,000 more job vacancies than before the pandemic. While wage growth remains moderate, the budget released just early this week is expansionary and could add to the inflationary pressures. The war in Ukraine has led to a massive humanitarian crisis. It is a great source of uncertainty and added (petrol and food) inflation to the world economy.

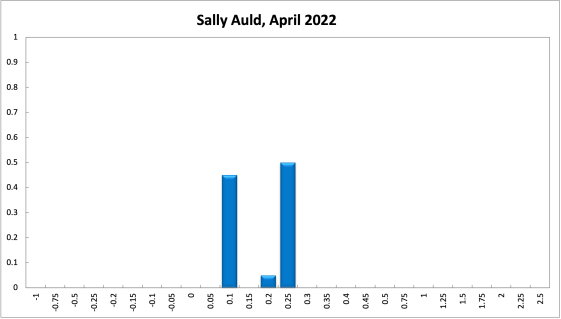

Within the next 3 to 6 months, we’ll see whether inflation in Australia remains within the 2 to 3 per cent target rate or whether it actually goes above target. Hopefully by then, the political and economic uncertainty is lower. Given all these, my view is that it is appropriate for the cash rate not to change in the next meeting. However, it will be also appropriate to spell out under which economic conditions the rate will increase as this may need to happen earlier than anticipated.

The incoming data continues to show the underlying strength in the economy. While it will take a little longer for WPI wages growth to pick-up, due to the sticky nature of collective agreements and the award wage process, there are clear signs of momentum in the private sector (particularly in construction, professional services and parts of manufacturing). These trends are likely to be reinforced by the inflationary environment globally, with many local businesses now looking to pass on rising costs to final consumers.

Set against the backdrop of an upcoming election, the Federal budget included tax cuts and increased transfers for households; the strength of the economic recovery and the tailwind from elevated commodity prices means that despite these measures (and increases in funding for infrastructure, healthcare and cyber security) the deficit is not projected to worsen in FY23. While these payments will help offset the rising cost of living, given that the economy is operating close to full employment (and generating some domestic inflationary pressures as a result) there is a risk that they further fuel inflation.

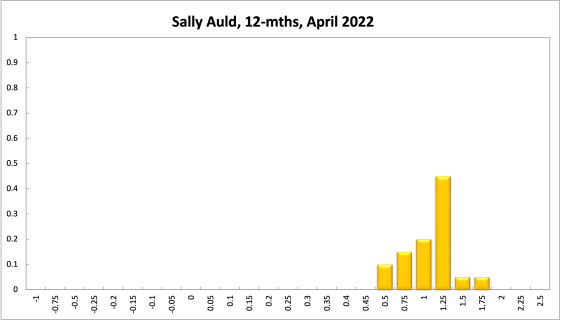

Given current conditions, it is appropriate for the RBA to begin raising the cash rate in the very near term, and to proceed with a steady pace of monetary tightening into 2023. While growth momentum will naturally ease in H2 2022 and again in 2023 as fiscal policy tightens, the RBA will need to return the cash rate to a broadly neutral stance over the medium term to ensure that inflation remains in check.

The just-released federal budget maintains a substantial deficit, despite higher than expected revenues due to commodity prices and an unemployment at 4%. Given relatively little slack in the economy, the main effects of the budget deficit will be higher inflation (headline and underlying) rather than to stimulate real activity. This provides a change in circumstances such that the RBA should consider beginning its raising cycle earlier than previously planned. It is true the RBA is still likely to wait for some indication of stronger nominal wage growth to pull the trigger. But that is almost certainly coming and will also imply higher real wage growth in 2023 and beyond given some easing of oil price and global supply chain effects on headline inflation later this year.

A change in government in May could mean a revised budget. But it is unlikely it would be particularly more fiscally responsible in the short term. So there is now a nontrivial chance that the RBA could and should start raising rates within the next six months, although I would still put this at below 50/50 odds given the need for wage growth to really pick up, while wages are generally slower to adjust in Australia than, say, the US given the different structure of the labour market.

However, the profligate budget does mean that liftoff will almost surely happen sooner than previously expected and likely in late 2022 or early 2023.

Updated: 18 July 2024/Responsible Officer: Crawford Engagement/Page Contact: CAMA admin

Cash Rate to Stay at Historic Low, But Not for Much Longer

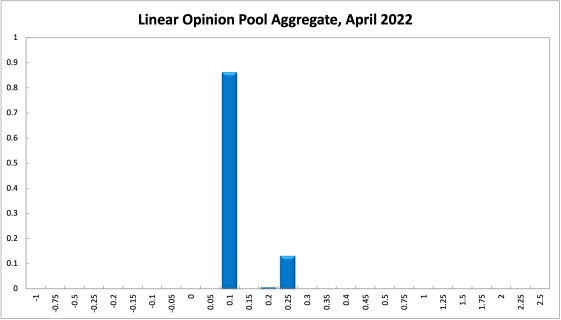

There is no new data on Australian CPI inflation, the most recent reading being 3.5% (headline, annual) and 2.6% (trimmed mean, annual) in the December quarter of 2021, above (within) the RBA’s official target band of 2-3%. GDP grew by 3.4% in the December quarter of 2021, exceeding market forecasts of around 3%. The RBA Shadow Board’s verdict is, once again, strongly in favour of keeping the cash rate steady at its historic low; it is 86% confident that this is the appropriate policy setting. However, at longer time horizons the Shadow Board’s consensus is shifting towards a tightening of the monetary stance.

The official ABS unemployment rate dropped from 4.2% in January to 4% in February, and it is projected to fall further. Youth unemployment, however, was unable to break below 9% in the same period. Total employment grew by more than 75,000, with full-time employment actually increasing by an impressive 122,000. The increase in employment and fall in unemployment coincide with a rise in the labour force participation rate of 0.2 percentage points, to 66.4%. The underemployment rate remains within the 6.5-7% range. Monthly hours worked increased by nearly 9%, which is a very significant improvement. There is no new data on (nominal) wages growth, which will be a key variable to look at in the coming months.

The Aussie dollar found strong support near the 70 US¢ mark and has recently climbed to 75 US¢. Matching the global trend, yields on Australian 10-year government bonds extended their climb, from a recent low of approx. 1.65% three months ago to 2.84% on the last day of March. Yield curves retain their normal convexity. Interest rate spreads have widened for shorter maturities: for short-term maturities (2-year versus 1-year) the spread is now 77.6 points; in mid-term versus short-term maturities (5-year versus 2-year) the spread is 78.8 bps, whereas for higher-term maturities (10-year versus 2-year) the spread fell to just below 100 bps. In the Australian share market initial losses following the invasion of Ukraine were recovered, a picture replicated elsewhere in the world. The S&P/ASX 200 stock index is again trading just below 7,500, some 500 points above its low one month ago.

The pre-election federal budget announced earlier this week is expansionary, as widely expected, including tax cuts and transfers to boost household disposable incomes as well as substantive spending programs on infrastructure, healthcare, and defence. This is not expected to increase the fiscal deficit in the coming fiscal year, a reflection of strong revenue growth, but it does add to overall inflationary pressures in the domestic economy.

Globally, the early jitters precipitated by the Ukraine war appear to have subsided a little. However, considerable downside risks for the global outlook remain, both due to Covid-19 and due to geopolitical forces. Severe bottlenecks, e.g. in the semi-conductor industry, will take a while to unblock, and energy and food prices can be expected to remain high and volatile. There is substantial disagreement among economists and policy makers about the likely duration of current inflationary pressures. The Federal Reserve has, after US inflation recorded a 40-year high, raised the federal funds rate and it has clearly indicated this is the beginning of a longer tightening cycle. The ECB may follow, albeit with a delay and less aggressively. So far, the RBA has remained sanguine about domestic inflation, arguing that it is transitory, but this view will need to be re-evaluated with new price and wages data coming out mid-year.

Australian consumer confidence dropped a little; the Melbourne Institute and Westpac Bank Consumer Sentiment Index fell from 101 to 96.6 in March. Retail sales growth is holding up, coming in at 1.6% in January and 1.8% in February, month-on-month. NAB’s index of business confidence, which tends to be volatile, continued its rebound, from -12 in December and 3 in January to 13 in February. The services and manufacturing PMIs both improved by around 3 points. The capacity utilization rate increased yet again by close to a full percentage point, to 82.51% in February. Mixed news comes from the Westpac-Melbourne Institute Leading Economic Index, considered a pretty reliable cyclical indicator for the Australian economy, which contracted by 0.2% year-on-year in February 2022, and the IHS Markit Australia Composite PMI, which, with a reading of 57.1 in March (a 10 month high), is strong. Overall, these indicators are pointing to a healthy expansion.

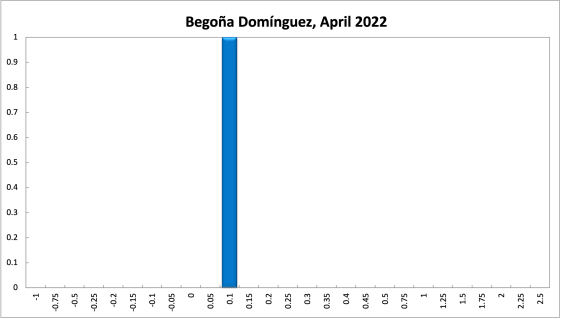

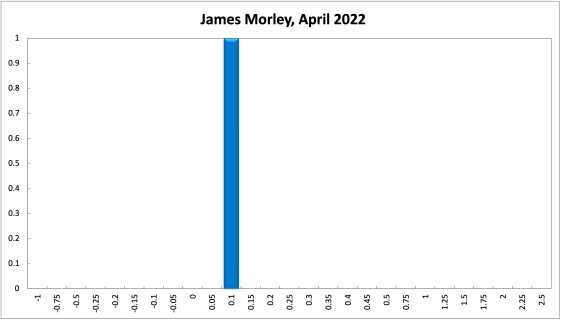

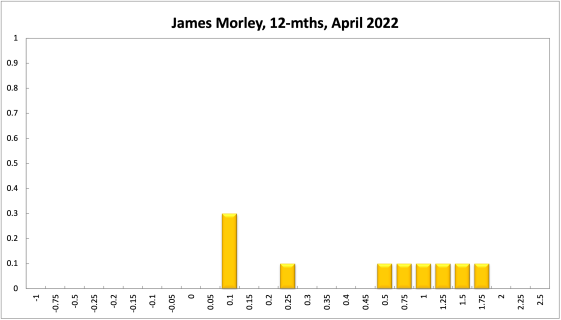

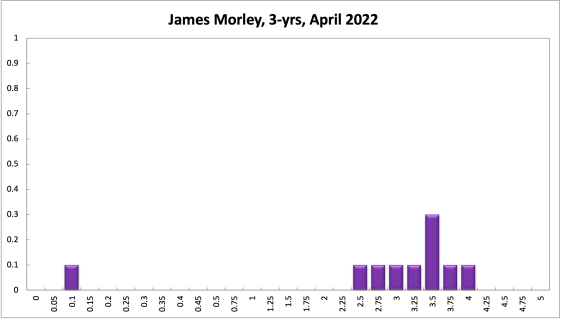

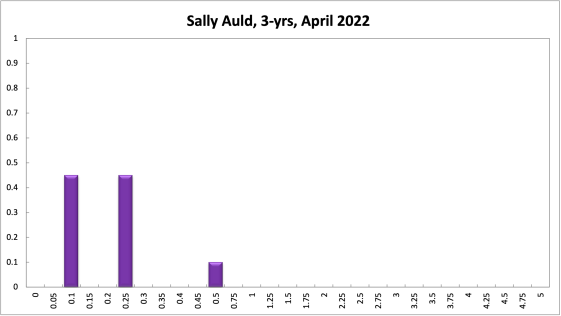

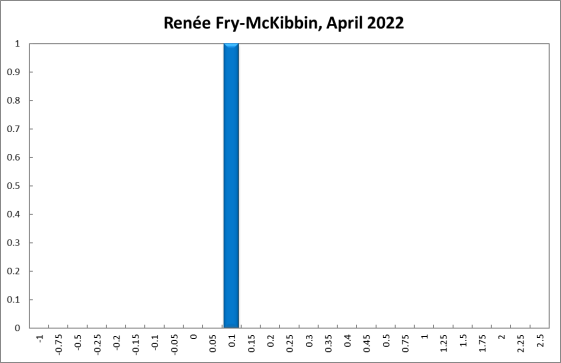

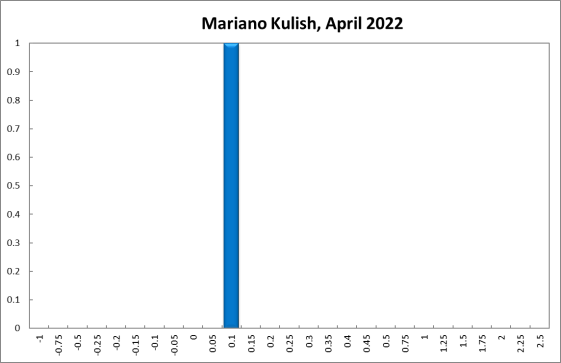

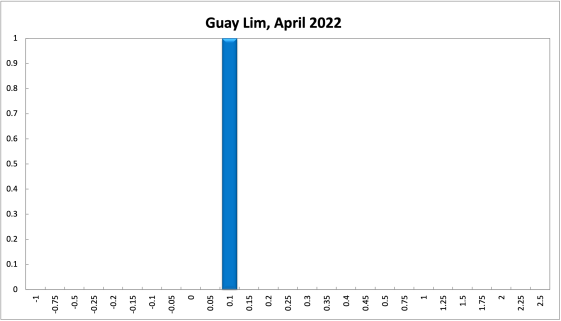

The official cash rate target has been at the historic level of 0.1% for 16 months. The Shadow Board’s conviction to keep the overnight interest rate at this historic low strengthened marginally. It attaches an 86% probability that “no change” is the appropriate policy (up from 83%) and a 13% probability that an increase is appropriate (down from 17%).

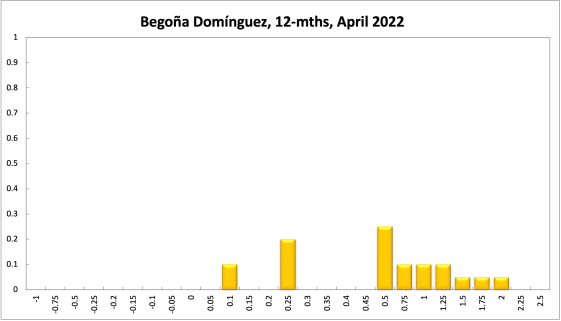

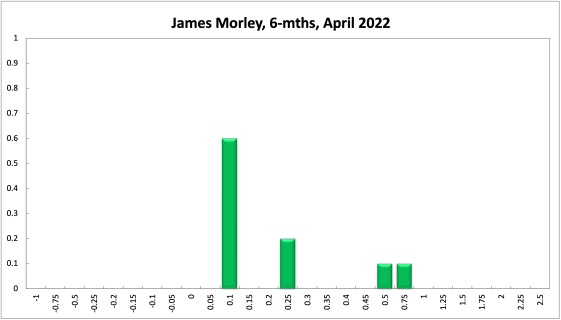

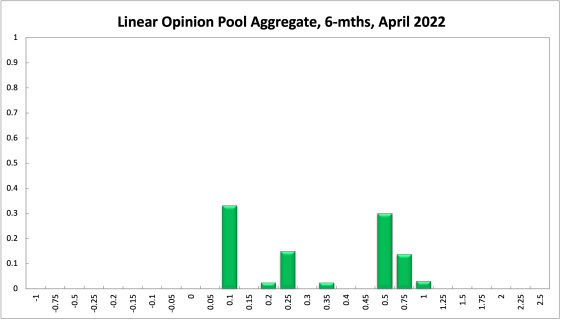

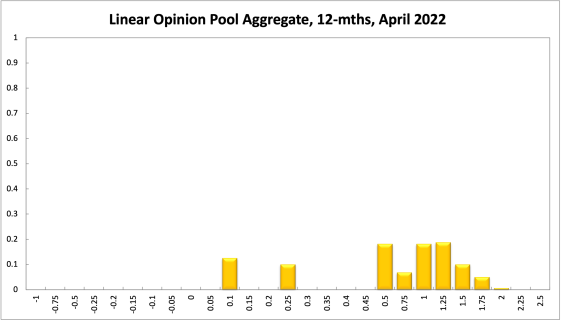

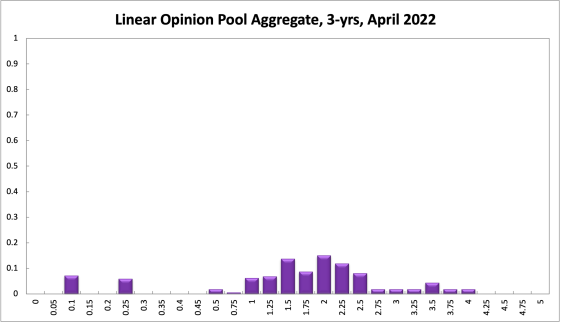

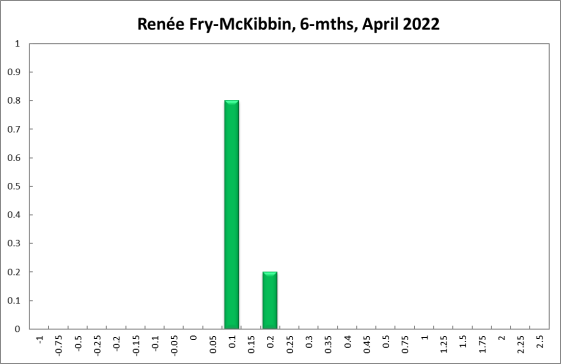

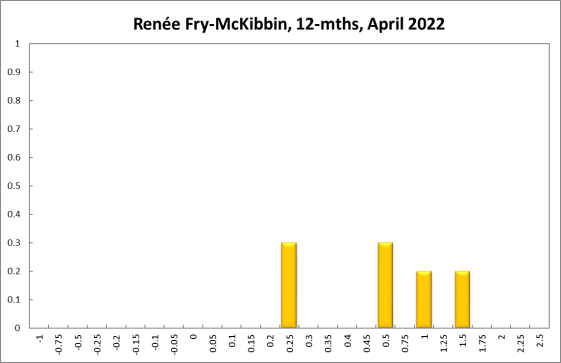

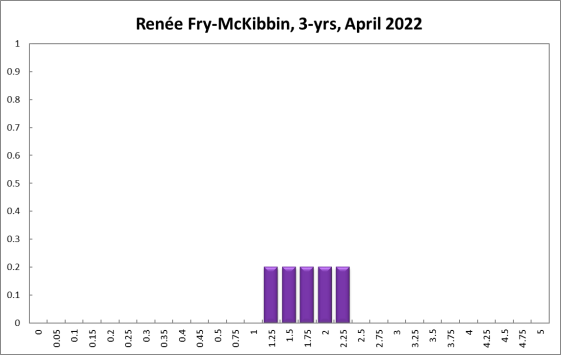

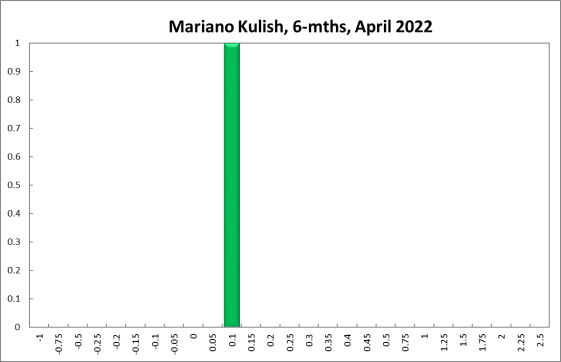

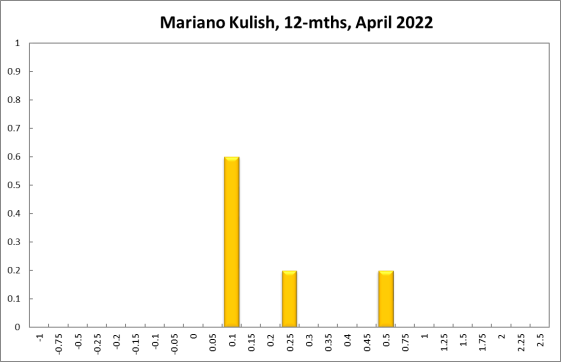

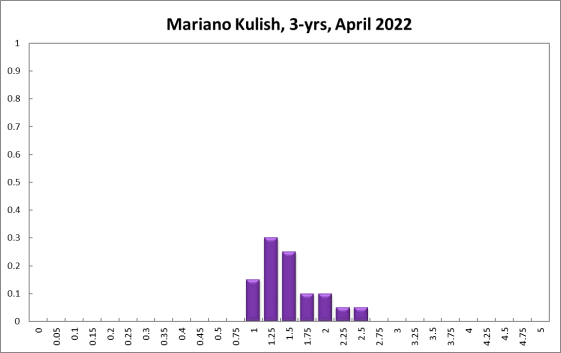

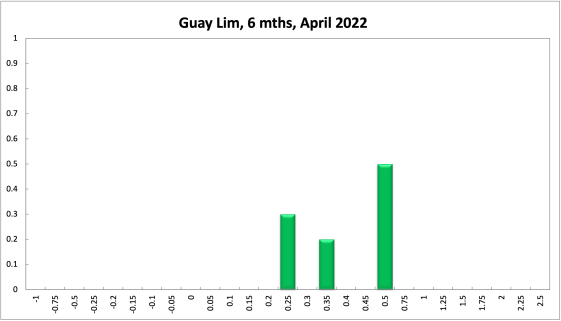

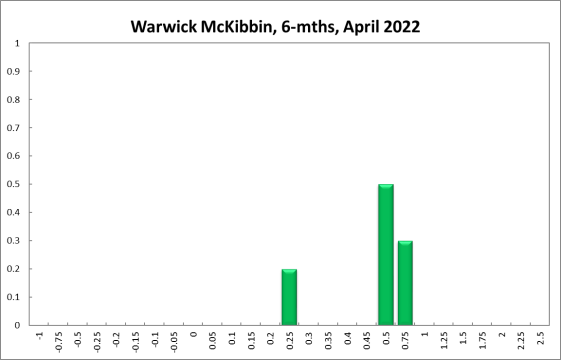

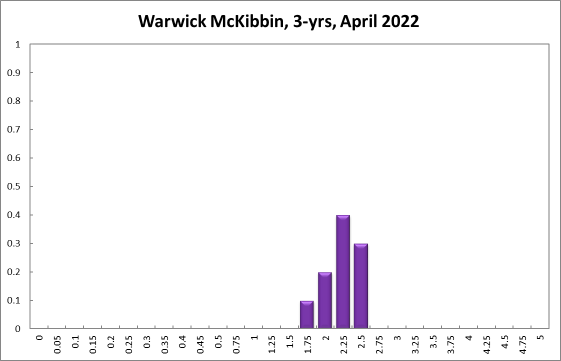

The probabilities at longer horizons are as follows: 6 months out, the confidence that the cash rate should remain at 0.1% weakened substantially, from 51% in March to 33% in the current round; the probability attached to the appropriateness of an interest rate decrease remains unchanged at 0%, while the probability attached to a required increase correspondingly rose from 49% to 67%. One year out, a similar picture emerges. The Shadow Board members’ confidence that the cash rate should be held steady dropped again, from 33% in March to 13% in this round. The confidence in a required cash rate decrease, to below 0.1%, is 0% (unchanged) and in a required cash rate increase 88% (67% in March). Three years out, the Shadow Board attaches a 7% probability that the overnight rate should equal 0.1% (down two percentage points) and a 93% probability that a rate higher than 0.1% is optimal (up three percentage points). The range of the probability distributions widened: for the 6-month horizon it extends from 0.1% to 1%, for the 12-month horizon from 0.1% to 2% and for the 3-year recommendation from 0.1% to 4%.