Outcome

The omicron wave has created significant short term challenges for the economy, with both consumer confidence and domestic supply chains taking a knock. But as has been seen in other parts of the world, the impact is likely to be temporary and the economy will be able to bounce back; domestic supply chain challenges are already easing (although they remain stretched), and the weekly consumer confidence and spending indices are now recovering.

The policy settings remain very supportive. Traditional fiscal supports (spending on infrastructure, the increase in the instant asset tax write-off for businesses, additional government spending on healthcare etc) are still feeding through and although market rates have risen and there is increased volatility, monetary conditions remain relatively loose. Together with further increases in consumer spending, that are likely to materialise as people become used to living with COVID, the outlook for growth this year remains brisk.

With economic activity and employment now pushing beyond pre-COVID levels (meaning the spare capacity in the economy has largely been absorbed), domestic inflationary pressures are building, as highlighted in the latest CPI data for Q4 2021. While some of the contributions to headline inflation will ease (particularly fuel, where the pace of increase is already moderating), core inflation has picked up and is likely to run further. Wage increases are now driving rises in the cost of home construction, childcare and gardening services amongst others, and many businesses are reporting that they will have to raise their final output prices in response to significant increases in their cost base.

Given the current position of the economy, it is appropriate for the RBA to move decisively away from the emergency pandemic settings - they have done their job and are no longer needed - and back towards ‘business as usual’. It would be appropriate for the RBA to end its QE program in the very near term, and to begin raising the cash rate in the second half of 2022.

Headline year-on-year inflation of 3.5% has led to some calls for the RBA to start a raising cycle for its policy interest rate this year. However, this would be premature.

Underlying measures of inflation are closer to the midrange of the target (e.g., trimmed mean = 2.6%). But more importantly, it is entirely predictable that inflation will fall to lower levels now that the base effects of the initial Covid shock to the CPI have run their course. Also, the recent high quarterly inflation was primarily driven by large increases in new dwelling prices and petrol prices. Mechanically, these effects on inflation will disappear or possibly push inflation back below the target range if these prices do not continue to increase at the same rate or even reverse (likely with petrol prices).

The 10-year break-even inflation expectations measure is back up to 2.3%, which is welcome news for the RBA in trying to achieve its inflation target. But this financial market expectation is predicated on the RBA sticking to keeping rates “lower for longer” (i.e., not raising rates until the second half of 2023 at the earliest) and could fall back below the target range if the RBA adjusts its forward guidance policies too drastically.

Global indicators of supply chain pressures also may be peaking (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-01-05/supply-chain-lates...).

All in all, the latest data suggest the RBA is on course to bringing inflation sustainably into its target range. But it is important that the RBA stays the course in it forward guidance policies to ensure inflation expectations remain aligned with the inflation target and, as frequently noted by the RBA, these expectations translate more strongly into sustained (real) wage growth.

With inflation having been below the RBA’s target range for almost 6 years and having now only just reached into the range, the RBA should reject pressure to raise the cash rate too soon. The US Federal funds rate will have to start rising this year given the excessive fiscal and monetary policy accommodation in place there, and this will tighten financial conditions even in Australia. But the RBA needn’t match the Fed, and can afford to allow some weakening in the currency. Assuming the unwinding of health and supply chain shocks by 2023, the time to think about normalising the cash rate is in 2023.

Updated: 26 December 2024/Responsible Officer: Crawford Engagement/Page Contact: CAMA admin

Cash Rate To Stay at Historic Low A While Longer in Face of Rising Inflation

The annual (headline) inflation rate in Australia rose to 3.5% in the December quarter of 2021, up from 3% in the previous quarter and higher than market estimates. This is well above the RBA’s official target band of 2-3%. However, the RBA’s trimmed mean CPI inflation, an inflation measure which excludes extreme (and typically volatile) values, increased to 2.6%, barely above the target band’s midpoint. The most recent available GDP growth data is the 1.9% contraction measured in Q3 of 2021, when much of the Australian population was in lockdown. GDP growth for Q4 is expected to look much more favourable. The RBA Shadow Board’s verdict is, once again, unchanged from the previous month: it has little doubt (94% confident) that keeping the cash rate at the historically low rate of 0.1% is the appropriate policy for the February round.

The labour market continues to improve; the most recent official ABS unemployment rate fell from 4.6% in November to 4.2% in December. Youth unemployment had also fallen substantially, to 10.9% in November. Total employment grew by nearly 65,000, two thirds of which was full-time. Significantly, the underemployment rate also tumbled for a second consecutive month, to 6.6%, while monthly hours worked increased by approximately 18 million hours, or 1%. Job advertisements surged by nearly 10% in November, and contracted by 5.5% in December. New data on wages growth will not be released until 23 February, but the tighter conditions in the labour market, coupled with an uptick in inflation, suggest we should see an increase in (nominal) wages growth.

The Aussie dollar, after a short rally in December, retreated to where it was two months ago, to around 70 US¢. Yields on Australian 10-year government bonds climbed from a recent low of approx. 1.65% to 1.97%. The yield curves, all of which are showing ‘normal’ convexity, have consequently become a bit steeper. Interest rate spreads have shifted along the maturity profile: for short-term maturities (2-year versus 1-year) the spread is now 32.1 points; in mid-term versus short-term maturities (5-year versus 2-year) the spread is 73 bps and in higher-term maturities (10-year versus 2-year) the spread narrowed to 100 bps. The Australian share market joined other markets worldwide in their recent decline; the S&P/ASX 200 stock index is now trading barely below 7,000, well below the 7,600 high reached in early January.

Risks to the global economy remain considerable, despite many advanced economies rebounding in 2021. On the one hand, Covid-19 poses a continuous challenge. New variants may continue to push back the end of the pandemic and vaccination rates in many developing nations, especially in Africa, are dangerously low to this day. Global supply chains are fractured and are partly contributing to the increase in global inflation. The military and diplomatic stand-off at the Ukrainian border is a real threat to regional peace. This is reflected in high energy prices, which in turn is fuelling headline inflation, and widespread sell-offs in global financial securities. Consensus is now growing that the Federal Reserve in the US will start tightening monetary policy as early as March 2022, adding pressure on other central banks, including the RBA, to follow suit.

Australian consumer confidence softened only slightly, with the Melbourne Institute and Westpac Bank Consumer Sentiment Index falling from 104 to 102 in January. New data on retail sales, which increased by an exceptional 7.3% month-on-month in November, will not be released until next week but are expected to be noticeably weaker. NAB’s index of business confidence plunged in December, from 12, to -12, a direct consequence of the omicron wave. The services PMI and manufacturing PMI are also two months old, so do not offer a reliable reading of the current state of services and manufacturing activity. The rebound in activity, until omicron hit the country, was pronounced – the capacity utilization rate increased more than one-and-a-half percentage points in November, to 83.15, after a jump of more than three percentage points in the previous month. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Leading Economic Index dropped 0.03% month-on-month in December of last year. The IHS Markit Australia Composite PMI dropped by a full 10 points in January 2022, from 55.1 to 45. All this points to a healthy economic rebound being thwarted by omicron in a short space of time. If predictions that the current Covid-19 wave is about to peak soon prove true, then consumer and business confidence should lift swiftly and put the Australian economy back onto its tracks.

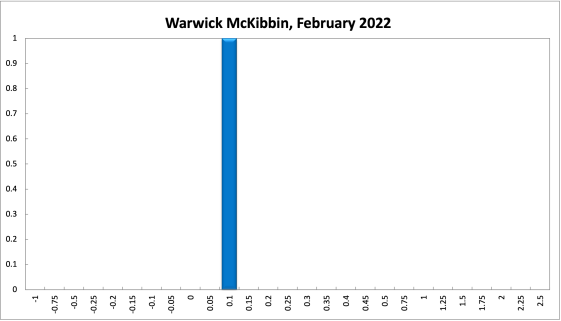

The official cash rate target has been at the historic level of 0.1% for 14 months. While it continues to be very confident that the overnight interest rate should remain steady this round, the Shadow Board’s conviction – in light of recent inflation data – has weakened slightly. It attaches a 94% probability that “no change” is the appropriate policy (down from 100%) and a 6% probability that an increase is appropriate (up from 0%).

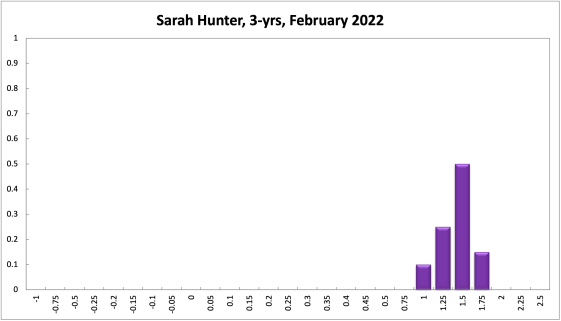

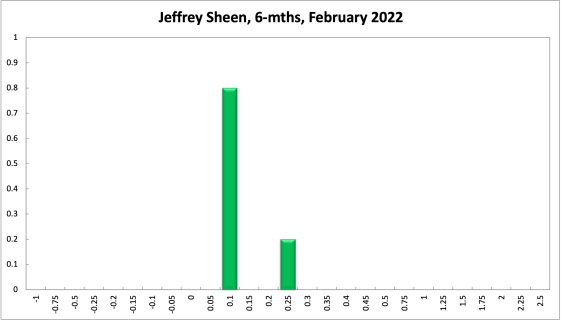

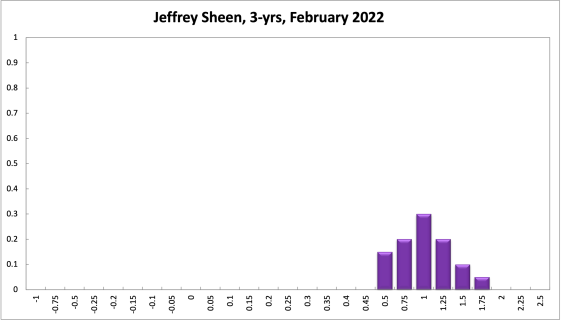

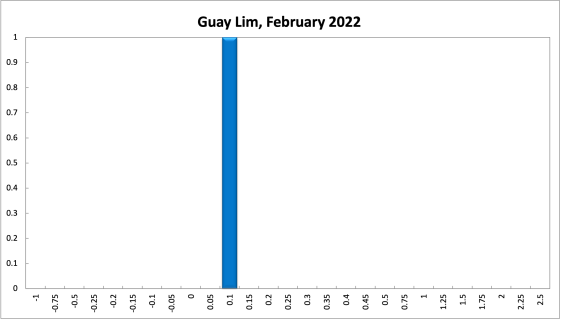

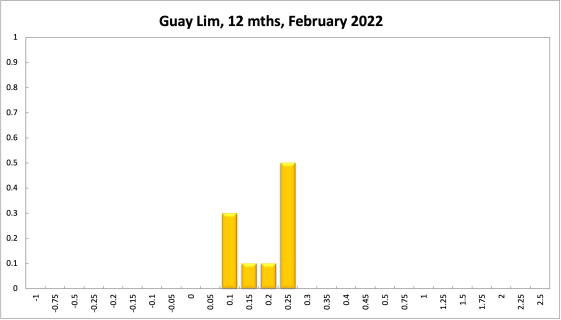

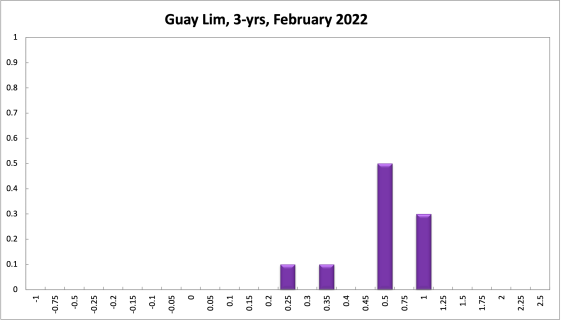

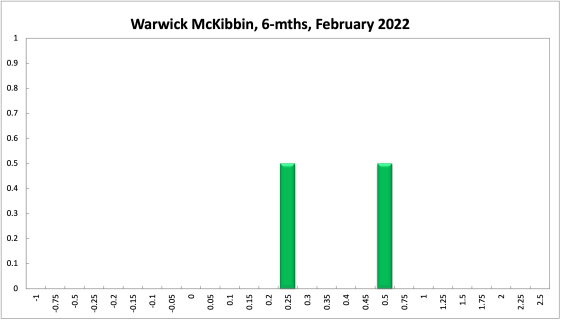

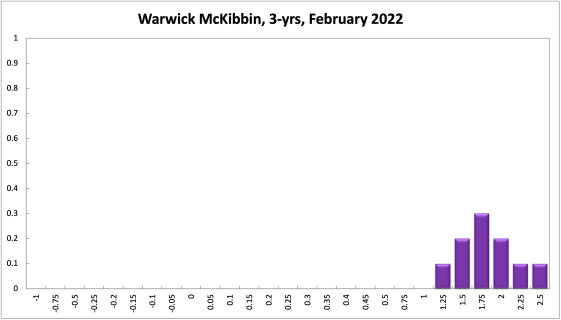

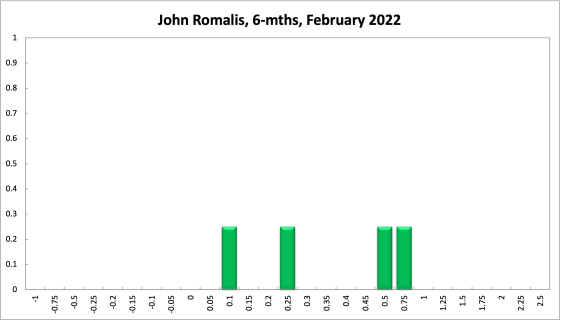

The probabilities at longer horizons are as follows: 6 months out, the confidence that the cash rate should remain at 0.1% has softened further, from 75% in December to 59% in the current round; the probability attached to the appropriateness of an interest rate decrease remains unchanged at 0%, while the probability attached to a required increase rose from 25% to 41%. One year out, the Shadow Board members’ confidence that the cash rate should be held steady also fell, from 50% in December to 39% in this round. The confidence in a required cash rate decrease, to below 0.1%, is 0% (unchanged) and in a required cash rate increase 61% (50% in November). Three years out, the probabilities shifted in the same direction: the Shadow Board attaches a 2% probability that the overnight rate should equal 0.1% (down three percentage points), a 0% probability that a rate lower than 0.1% is appropriate, and a 98% probability that a rate higher than 0.1% is optimal (up three percentage points). The range of the probability distribution for the 6-month horizon widened slightly, extending from 0.1% to 0.75%, but remained unchanged for the 12-month horizon, from 0.1% to 2%. For the 3-year recommendation, the distribution again remains unchanged, extending from 0.1% to 2.5%.