Outcome

The deterioration of the COVID situation in Sydney (and spillovers to other regions and states) has materially impacted the near term outlook for the economy. GDP will almost-certainly contract in the September quarter, and given the transmissibility of the delta variant (and the resultant risk of further outbreaks from quarantine) it is likely that significant restrictions will have to remain in place in a number of states until the vaccine rollout is significantly more progressed.

Given the heightened uncertainty, it is appropriate for the RBA to moderate the pace of any monetary tightening it was previously considering. While this implies no change to the cash rate in the near term, the Board should look to delay any further winding back of the QE program.

Over the medium/long term, the encouraging data from the UK, the US and other countries with respect to vaccine efficacy (that is, the breaking of the link between cases of COVID and hospitalisations and adverse outcomes) suggests that once the vaccine rollout has progressed it will be possible to sustainably relax restrictions and reach a ‘new normal’. Assuming fiscal policy settings remain accommodative (including the roll out of disaster payments and grants for businesses), the strength of the recovery in H1 2021 suggests that the economy has the capacity to bounce back strongly, as such my assessment on the outlook for 2023 and beyond is broadly unchanged, although the timing of the recovery is more uncertain given it is now much more contingent on the success of the vaccination program.

The slow speed of vaccine rollout in Australia and the emergence of the delta strain of Covid-19 combined with a worsening global situation means interest rates are likely to remain lower for longer. There will likely be continuing emergence of new strains of the virus in developing countries where Covid-19 remains out of control. The response of worsening health outcomes will dampen economic activity in Australia independently of whether the State government implement lockdowns. The loss of consumer and business confidence implies a need for fiscal and monetary support in Australia for a much more extended period than I had hoped earlier in the year. I would not be surprised to see a W recovery rather than a continuation of the V recovery to date. There is nothing that the RBA can do to offset this outcome apart from maintaining financial stability. It is up to fiscal policy and income support policy for businesses and households to prevent a W-shaped recovery.

Q2 inflation was just released and the headline number was a 3.8% year-on-year rate. While this is above the RBA’s target range of 2-3% and some temporarily higher inflation is welcome to bring the price level back to where it was expected to be prior to the crisis, it is clear that much of this headline number is a temporary spike due to a “base effect” (the CPI was particularly low in 2020Q2 due to the Covid crisis, including measurement issues for prices of goods and services for which exchange was disrupted by the crisis). To see this base effect, note that the CPI suggests prices are only 3.5% higher than they were two years ago in 2019Q2, which corresponds to an annualised inflation rate of only 1.7% over the last two years.

The key for the RBA is that measures of inflation expectations have increased, including a return back up to the (low end of) its 2-3% target range for the break-even 10-year inflation rate of 2.1% in Q1 and sustained at 2.0% in Q2.

Also, the decline in the unemployment rate to 4.9% in June is particularly welcome news, but the economic fallout from the Delta variant is likely to be negative real GDP growth in Q3 and an increase in the unemployment rate. So the RBA’s forward guidance to keep the policy rate at 0.1% until at least 2024 remains an appropriate setting.

Updated: 21 November 2024/Responsible Officer: Crawford Engagement/Page Contact: CAMA admin

Sydney Covid-19 Outbreak Puts Brakes on Economic Recovery: Cash Rate Must Stay On Hold

Sydney’s Covid-19 outbreak, fuelled by the highly contagious Delta strain, is forcing the city into a protracted lockdown, costing lives, jobs and livelihoods and putting the brakes on what was a strong economic recovery in Australia. Given the lagged nature of most economic indicators, the fallout from this outbreak is not fully reflected in the most recent economic data. Inflation, as measured by the growth rate of the CPI, surged to 3.8% (year-on-year) in the June quarter, above the RBA’s official target band of 2-3%, for the first time in nearly ten years. The RBA Shadow Board’s resolve to keep the cash rate at the historically low rate of 0.1% has strengthened: it is near-certain (98% subjective probability) that this is the appropriate policy in August.

There was more positive news from the Australian labour market in June. The official ABS unemployment rate for that month came in at 4.9%, a drop from 5.1% in May. Youth unemployment improved slightly as well, falling by half a percentage point, to 10.2%. Total employment increased by nearly 30,000, while the labour force participation rate remained steady at 66.2%. Job advertisements rose by 3% month-over-month, after the previous month’s figure had to be revised downward by 6.8%, making it the 13th consecutive month of an increase in job ads. New figures on real wage growth are not released until 12 August, with the RBA expecting growth in the Wage Price Index (WPI) to increase slightly to just under 2% over 2021.

The Aussie dollar continued its recent decline, falling to below 74 US¢. Yields on Australian 10-year government bonds have likewise dropped, to below 1.2%, suggesting that market participants’ future inflation expectations continue to fall. This lessens the pressure on the RBA to increase interest rates in the near future. The broad shapes of the yield curves are unchanged: the yield curve in short-term maturities (2-year versus 1-year) remains flat by policy design; in mid-term versus short-term maturities (5-year versus 2-year) and in higher-term maturities (10-year versus 2-year) the yield curves continue to display normal convexity. The spread between the 10-year rate and the 2-year rate shortened yet again, from 138 basis points to 116 basis points. The Australian stock market, on the other hand, broke new highs, with the S&P/ASX 200 stock index closing well above 7,400.

In its July World Economic Outlook Update, the International Monetary Fund announced that it is projecting the global economy to grow 6% in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022, but it also warned that growth will be uneven, as the gap between rich and poor countries was widening amid the pandemic. A major contributing factor is the low vaccination rates in emerging economies. Dr Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s chief economist, wrote in the report that, “multilateral action is needed to ensure rapid, worldwide access to vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics. This would save countless lives, prevent new variants from emerging and add trillions of dollars to global economic growth. The importance of a high vaccination rate for a country’s health and economy should serve as a clear warning to Australia.

Australian consumer confidence stabilised a bit: the Melbourne Institute and Westpac Bank Consumer Sentiment Index, after falling for two months, increased from 107 to 109 in July. NAB’s index of business confidence, however, continued to drop, falling – after a recent high of 23 – from 20 to 11 in June. The services PMI fell from 61.2 in May to 57.8 in June; the manufacturing PMI has not been released yet but is also expected to fall slightly. Capacity utilisation also continued to diminish, from 85.1% in May to 83.9% in June. The Westpac-Melbourne Institute Leading Economic Index contracted for the second month in a row, by 0.07% month-over-month in June, following three months of improvements. The six-month annualised growth rate in the Leading Index equals 1.34% in June. The recent lockdowns in NSW and Victoria, however, are dampening the future outlook, with both states’ economies expected to contract in the September quarter, according to Westpac and the Melbourne Institute.

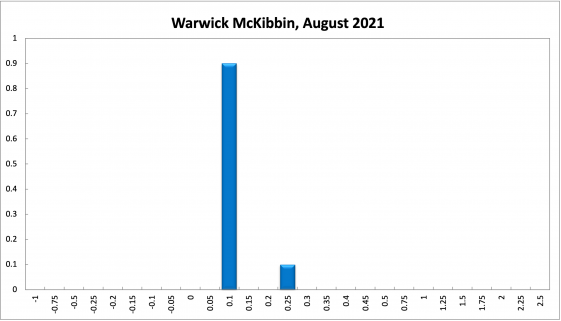

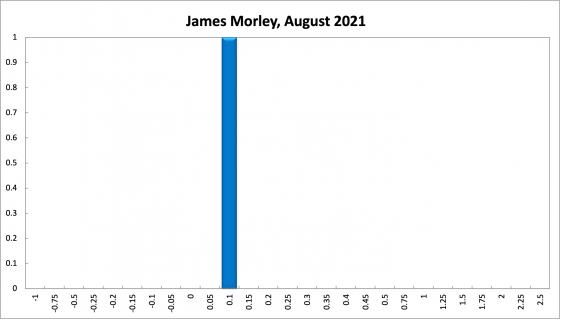

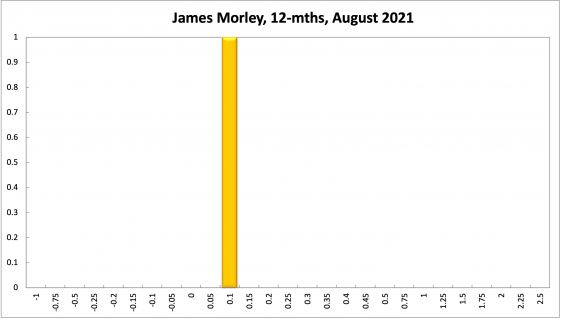

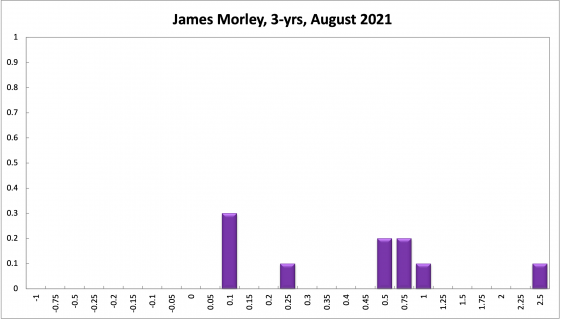

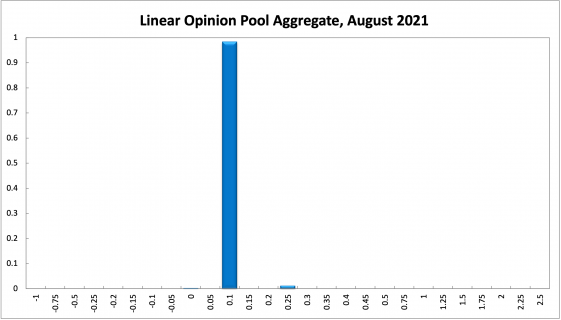

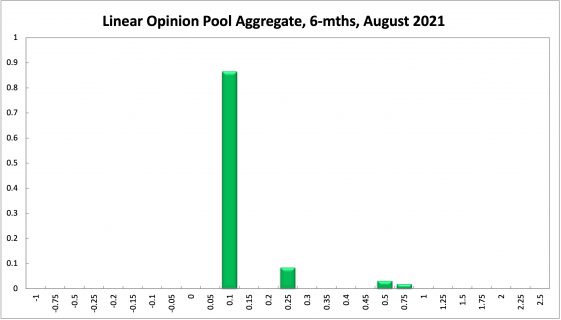

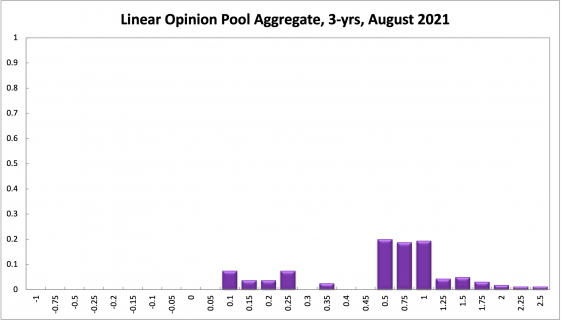

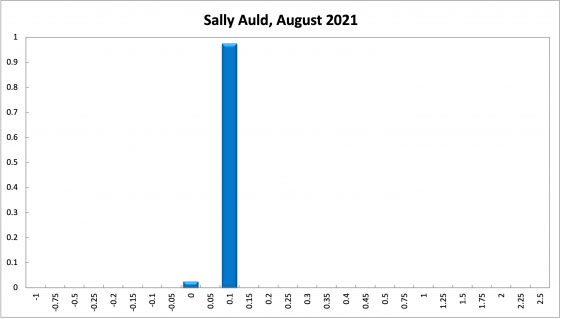

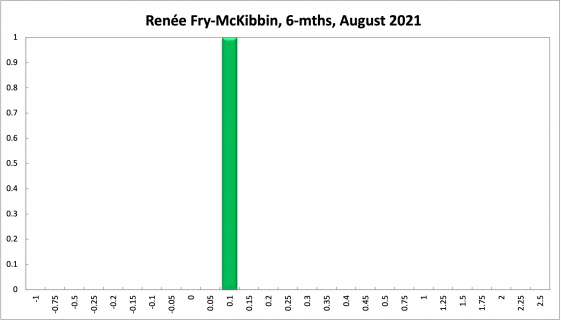

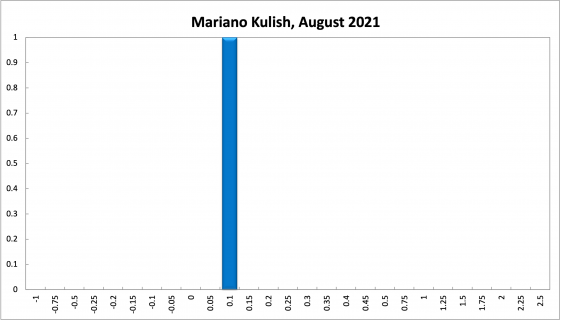

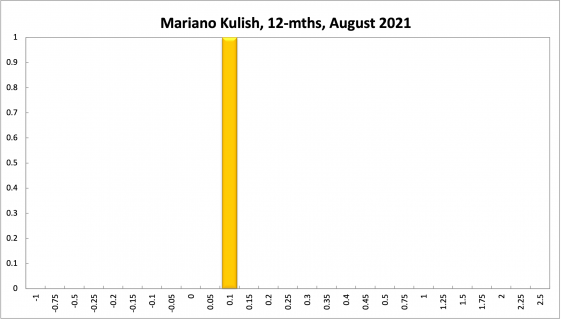

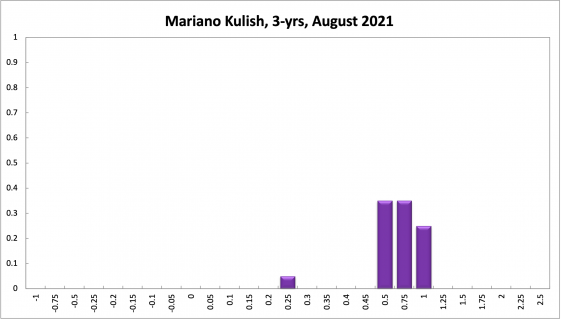

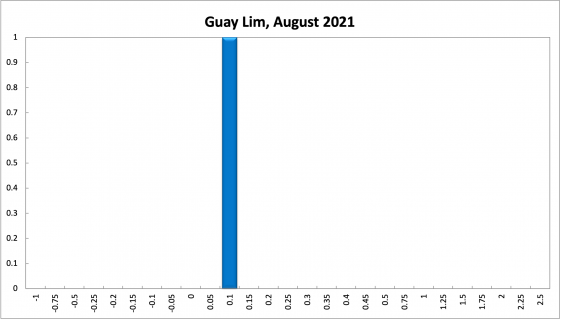

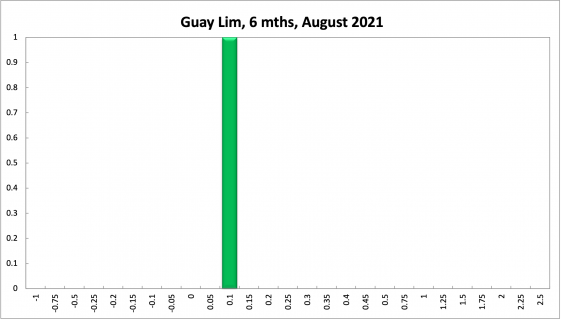

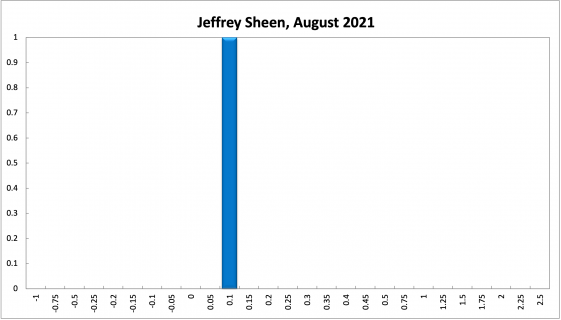

The official cash rate target has been at the unprecedented level of 0.1% for nine months. The Shadow Board’s already strong conviction to keep the overnight interest rate at 0.1% strengthened further: it attaches a 98% probability that the overnight interest rate should remain steady (94% in July), a 1% probabilty that an increase is appropriate (6% in July) and a 0% probability that a further rate cut to below 0.1% is appropriate.

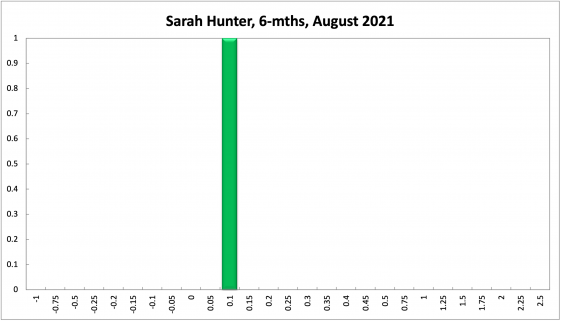

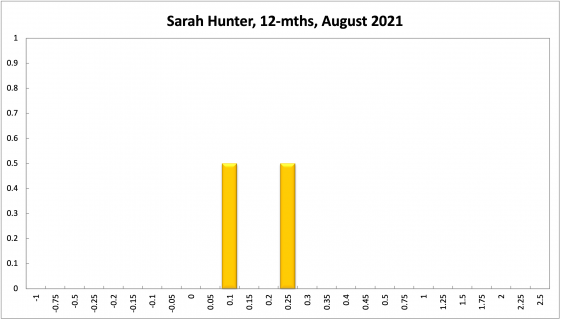

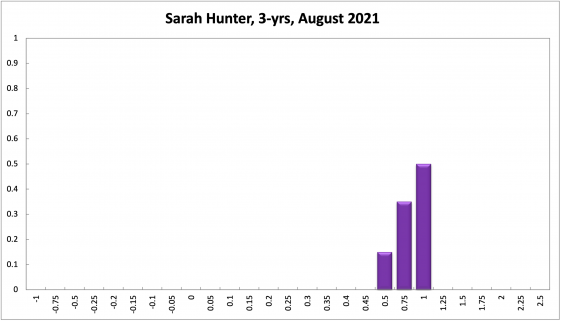

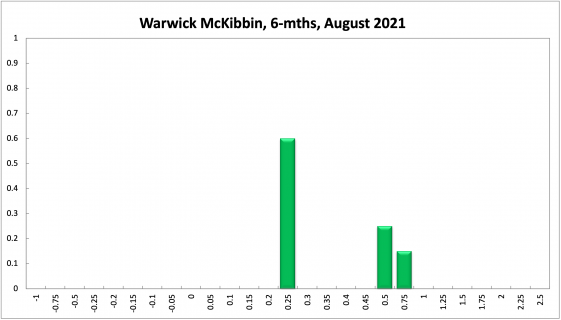

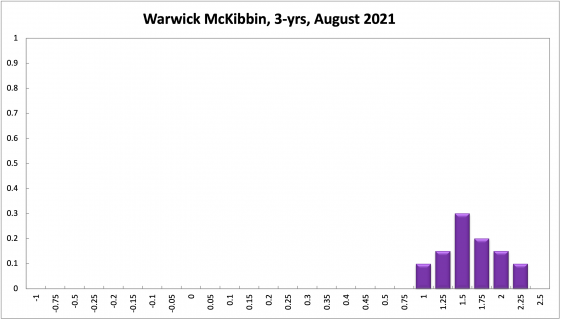

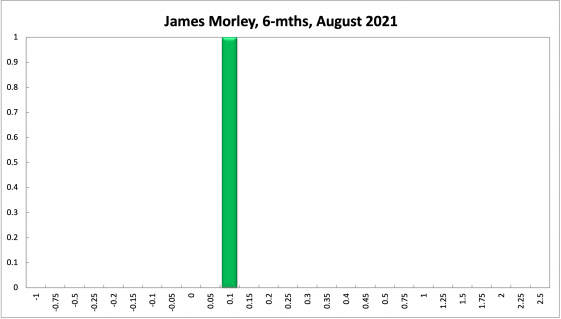

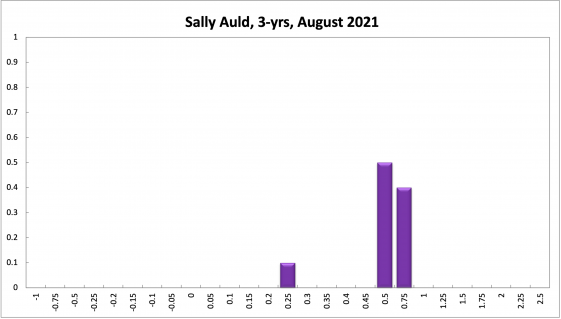

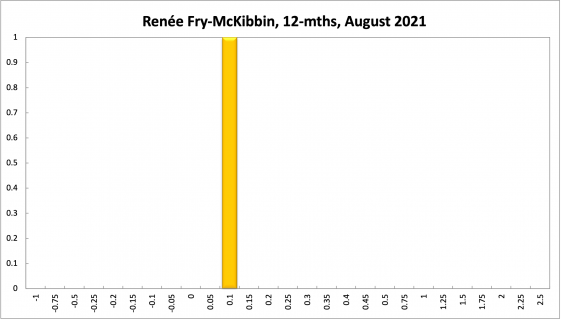

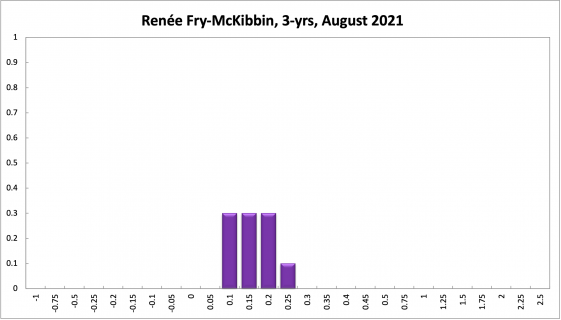

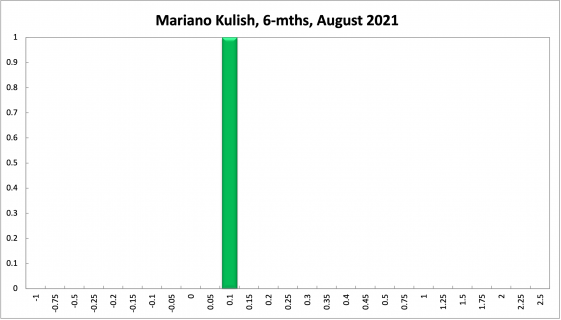

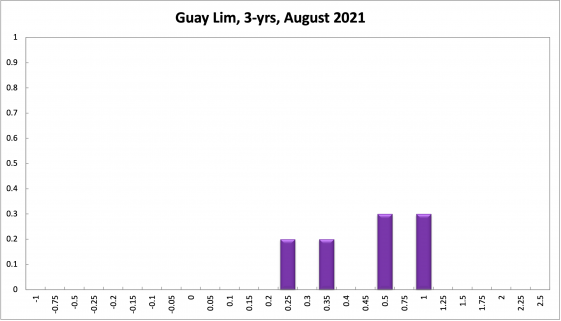

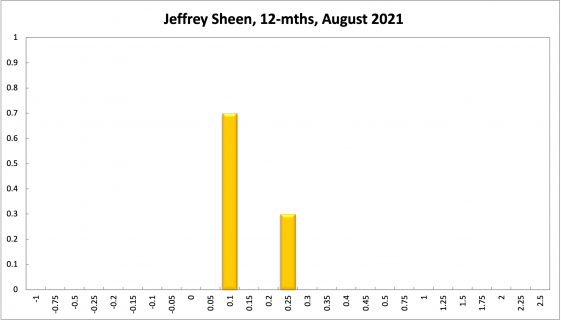

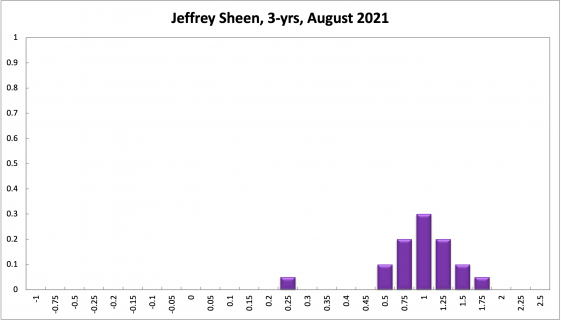

The probabilities at longer horizons are as follows: 6 months out, the confidence that The cash rate should remain at 0.1% has also strengthened, from 75% in July to 87%, the probability attached to the appropriateness for an interest rate decrease is exactly 0%, while the probability attached to a required increase dropped from 25% to 13%. One year out, the Shadow Board members’ confidence that the cash rate should be held steady equals 68% (58% in July). The confidence in a required cash rate decrease, to below 0.1%, is 0% (unchanged) and in a required cash rate increase 32% (42% in July). Three years out, the Shadow Board attaches an 8% (9% in July) probability that the overnight rate should equal 0.1%, a 0% probability that a rate lower than 0.1% is appropriate, and a 93% (91% in July) probability that a rate higher than 0.1% is optimal. The range of the probability distributions over the 6 month and 12 month horizons has contracted to 0.1-1%, and the range of the probability distribution for the 3-year recommendation is unchanged, extending from 0.1% to 2.5%.